The Endurance:

“McCarthy, the best and most efficient of the sailors, always cheerful under the most trying circumstances, and who for these very reasons I chose to accompany me on the boat journey to South Georgia, was killed at his gun in the Channel.”

“Cheetham, the veteran of the Antarctic, who had been more often south of the Antarctic Circle than any man, was drowned when the vessel he was serving in was torpedoed, a few weeks before the Armistice.”

“The two surgeons, Macklin and McIlroy, served in France and Italy, McIlroy being badly wounded at Ypres.”

“Frank Wild, in view of his unique experience of ice and ice conditions, was at once sent to the North Russian front, where his zeal and ability won him the highest praise.”

“Macklin served first with the Yorks and later transferred as medical officer to the Tanks, where he did much good work. Going to the Italian front with his battalion, he won the Military Cross for bravery in tending wounded under fire.”

“James joined the Royal Engineers, Sound-Ranging Section, and after much front-line work was given charge of a Sound-Ranging School to teach other officers this latest and most scientific addition to the art of war.”

“Wordie went to France with the Royal Field Artillery and was badly wounded at Armentières.”

“Hussey was in France for eighteen months with the Royal Garrison Artillery, serving in every big battle from Dixmude to Saint-Quentin.”

“Worsley, known to his intimates as Depth-Charge Bill, owing to his success with that particular method of destroying German submarines, has the Distinguished Service Order and three submarines to his credit.”

“Clark served on a minesweeper.”

“Greenstreet was employed with the barges on the Tigris.”

“Rickenson was commisioned as Engineer-Lieutenant.”

“R.N. Kerr returned to the Merchant Service as an engineer.”

“Most of the crew of the Endurance served on minesweepers.”

— Ernest Shackleton, South

Blackboro: On return from the Antarctic, Blackborow spent three months in a hospital in Punta Arenas, Chile, recovering from the frostbite damage sustained to his left foot. He volunteered for war service in the Royal Navy, but was turned down due to the amputation of the toes of his left foot. He was accepted by the Merchant Navy where he served until 1919.

Crean: Once again on his return to England, Crean resumed his naval career at Chatham. For the rest of the First World War, Crean served in the Royal Navy aboard HMS Colleen. In 1927 Tom opened a pub in Annascaul, “The South Pole Inn” (still in business today).

Orde-Lees: On return to England after the expedition, he served in the Balloon Service and saw action on the Western front. With Shackleton’s help, he joined the Royal Flying Corps (R.F.C.) and was a pioneering figure in parachute jumping. On one occasion, he jumped off the top of Tower Bridge into the River Thames, only about 160 or so feet below to convince the British Military of the usefulness of the parachute. Although this was just a stunt, it seemed to do the trick and the R.F.C. formed a parachute division with Orde-Lees in command.

McNeish: After the expedition McNish returned to the Merchant Navy and worked on various ships. He often complained that the extreme cold and soaking conditions he had experienced in the boat journey on the James Caird had left him so that his bones permanently ached. Other people who knew him say that he would often refuse to shake hands because of the pain.

Hurley: After the Expedition, Hurley became a noted army photographer in the First World War, then became the go-to photographer for expeditions to the tropic regions. He returned to the Antarctic in 1929.

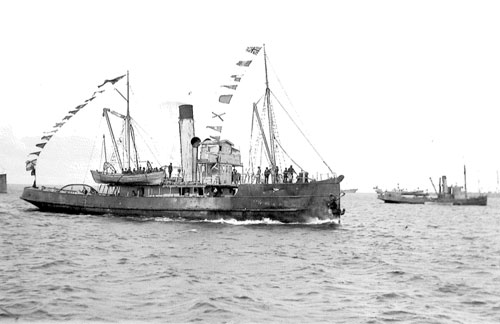

Hurley’s photos of WWI

Marston: On return from the expedition Marston taught at Bedales school in Petersfield from 1918 to 1922. In 1925, he joined the Rural Industries Bureau (RIB) as Handicrafts Adviser, having always been a lover rural life and countryside matters, he was appointed Assistant Director in 1931 and Director in 1934.

— www.coolantarctica.com

The Aurora:

“Stenhouse, who commanded the Aurora after Mackintosh landed, was with Worsley as his second in command when one of the German submarines was rammed and sunk, and received the D.S.C. for his share in the fight. He was afterwards given command of a Mystery Ship, and fought several actions with enemy submarines.”

“Ernest Wild, Frank Wild’s brother, was killed while mine-sweeping in the Mediterranean.”

“Mauger, the carpenter on the Aurora, was badly wounded while serving with the New Zealand infantry, so that he is unable to follow his trade again. He is now employed by the New Zealand government.”

“Hooke, the wireless operator, now navigates an airship.”

“Of the Ross Sea Party, Mackintosh, Hayward, and Spencer-Smith died for their country as surely as any who gave up their lives on the fields of France and Flanders.”

“Nearly all of the crew of the Aurora joined the New Zealand Field Forces and saw active service in one or other of the many theaters of war.”

— Ernest Shackleton, South

***

Read more:

Brief biographies of the crew of the Endurance at coolantarctica.com